Tessian’s CEO and co-founder Tim Sadler joined Dave Bittner from the CyberWire and Joe Carrigan from the Johns Hopkins University Information Security Institute to talk about why people make mistakes and the importance of developing a strong security culture.

“Security is serious business. No one would doubt or question its importance. It is literally mission critical for companies to get right.”

Tim Sadler

Tessian CEO and Co-Founder

Dave Bittner: Joe, I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Tim Sadler. He’s been on our show before. He’s from an organization called Tessian, and they recently published a report called “The Psychology of Human Error.” Here’s my conversation with Tim Sadler.

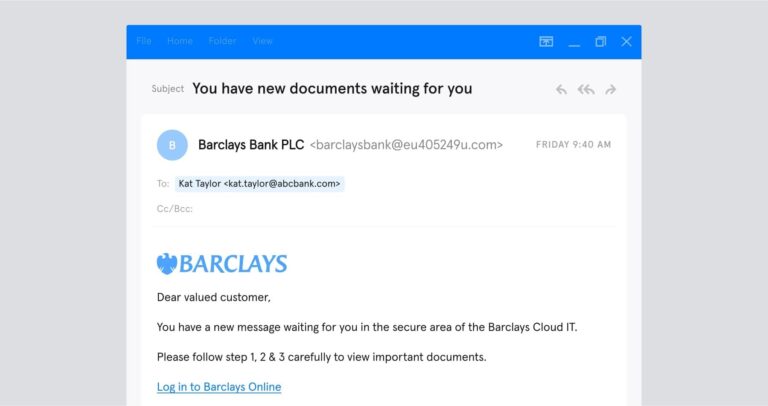

Tim Sadler: We commissioned this report because we believe that it’s human nature to make mistakes. The people control more sensitive data than ever before in the enterprise. So there’s customer data, financial information, employee information. And what this means is that even the smallest mistakes – like accidentally sending an email to the wrong person, clicking on a link in a phishing email – can cause significant damage to a company’s reputation and also cause major security issues for them. So we felt that businesses first need to understand why people make mistakes so that, in the future, they can prevent them from happening before these errors turn into things like data breaches.

Dave Bittner: Well, let’s go through some of the findings together. I mean, it’s interesting to me that, you know, right out of the gate, the first thing that you emphasize here is that people do make mistakes.

Tim Sadler: Absolutely, they do make mistakes, and I think that is human nature. We think about our daily lives and the things that we do; we factor in human error, and we factor in that we will make mistakes. And something I always come back to is if we think about something we do, you know, many of us do on a daily basis, which is, you know, driving a car, and we think about all of the assistive technology that we have in that car to protect us in the event that we do make a mistake because, of course, mistakes are expected. It’s kind of in our human nature.

Dave Bittner: Well, let’s dig into some of the details here because there are some fascinating things that you all have presented. One of the things you dig into is the age factor. Now, this was interesting to me because I think we probably have some biases about who we think would be more likely to make mistakes, but you all uncovered some interesting numbers here.

Tim Sadler: Yeah, completely. And, you know, just sharing some of those statistics that we found from this report, 65% of 18- to 30-year-olds admit to sending a misdirected email comparing to 34% who are over the age of 51. And we also found that younger workers were five times more likely to admit to errors that compromised their company’s cybersecurity than older generations, with 60% of 18- to 30-year-olds saying they’ve made such mistakes versus 10% of workers who are over 51.

Dave Bittner: Now, what do you suppose is the disparity there? Do you have any insights as to what’s causing the spread?

Tim Sadler: I think it is just speculation that I think there’s something interesting in just maybe thinking about the comfort level that younger workers might have with actually admitting mistakes or sharing that with others in the enterprise. You know, I think there’s something encouraging here, which is actually we’re seeing that if you were running a security team, you want your employees to come forward and tell you something has gone wrong, whether that’s a mistake that’s led to a bad thing or it’s a near miss. And I think that you also might find that, generally, younger people may tend to be less senior in the organization and, you know, may not have the same sense of stigma that maybe the older generations, who are more senior, may think there is. So if I tell my boss that, you know, I’ve just done something and there was a potentially bad outcome, they might feel like they may be in danger of compromising their position in the organization.

Dave Bittner: Yeah, it’s a really interesting insight. I mean, that whole notion of the benefits of having a company culture that encourages the reporting of these sorts of things.

“If you don't see people reporting anything, it's usually a more concerning sign than you have people coming forward who are openly admitting to the errors they've made that could lead to these security issues. It's highly unlikely that you've got nothing on your risk register. That you've completely eliminated risk from your business. It's more likely that actually you haven't created the right culture that feels like it's suitable or acceptable to actually come forward and admit mistakes. ”

Tim Sadler

CEO and Co-Founder

Tim Sadler: I think it’s so important. You know, I think – somebody, you know, correctly advised me, you almost need an everything’s-OK alarm in your business when you’re thinking about security. You know, if you have a risk register or if you are responsible for taking care of these incident reports, if you don’t see people reporting anything, it’s usually a more concerning sign than you have people coming forward who are openly admitting to the errors they’ve made that could lead to these security issues. It’s highly unlikely that you’ve got nothing on your risk register. That you’ve completely eliminated risk from your business. It’s more likely that actually you haven’t created the right culture that feels like it’s suitable or acceptable to actually come forward and admit mistakes.

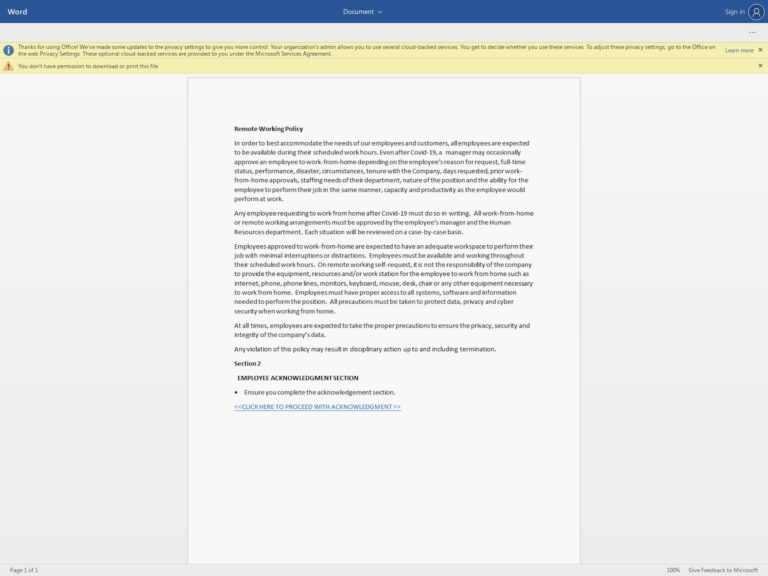

Tim Sadler: And I think this is really, really important. I think now more than ever, during this time where, you know, we have a global pandemic, a lot of people are working from home, and they’re kind of juggling the demands of their jobs with their personal lives – maybe they’re having to figure out childcare – there are lots of other things weighing in to an employee’s life right now. It’s really important to actually, I think, extend empathy and create an environment where your employees do feel comfortable actually sharing things, mistakes they’ve made or things that could pose security incidents. I think that’s how you make a stronger company, through that security culture.

Dave Bittner: But let’s move on and talk about phishing, which your report digs into here. And then this was surprising to me as well. You found that 1 in 4 employees say that they’ve clicked on phishing emails. But interesting to me, there was a gap between men and women and, again, older folks and younger folks.

Tim Sadler: Yes, so we found in the report that men are twice as likely as women to click on links in a phishing email, which again I think is – I think we were as surprised as you are that that was something that came from the research that we conducted.

Dave Bittner: And a much lower percentage of folks over 51 say that they’d clicked on phishing links.

Tim Sadler: Yes. And, again, you know, because of the research, of course, we’re relying on people’s honesty about these kinds of things.

Dave Bittner: Right.

Tim Sadler: But it does seem that there are clear kind of demographic splits in terms of things like age and also gender in terms of, actually, the security outcomes that took place.

Dave Bittner: I mean, that in particular seems counterintuitive to me, but when I read your report, I suppose it makes sense that, you know, people who have more life experience, they may be more wary than some of the folks who are just out of the gate.

Tim Sadler: I think that does play into things. I think that younger generations who are coming into the workplace, who are maybe even used to – you know, they’ve had an email account maybe for most of their lives. In fact, I would say that they’re probably less used to using email because they’ve advanced to other communication platforms before they enter the workplace. But I do think that, you know, if you think about people who have had email accounts, you know, at school or at college, they’re going to be used to being faced with potential scams, potential phishing. They’ve maybe already been through many kind of forms of education training awareness, those kinds of things, before they’ve actually entered the world of work.

Dave Bittner: Yeah, another thing that caught my eye here was that you found that tech companies were most fallible. And it seemed to be that the pace at which those companies run had something to do with it.

Tim Sadler: Yeah, I think there’s something interesting here. And, again, just would say that this is speculation because we don’t have the specific data to dig further into this. But I think there’s something interesting with the concept that technology companies, as you say, if they’re, you know, high-growth startups, they tend to be maybe moving faster, where these kinds of things can slip off the radar in terms of the security focus or the security awareness culture they create.

Tim Sadler: But the other thing – and I think something to be aware of – is sometimes technology companies have that kind of false sense of security that it’s all in check, right? ‘Cause they – you know, this is kind of their domain. They feel that it’s within their comfort zone, and then maybe they neglect, actually, how serious something like this could be, where they feel that, OK, we’ve actually – even if we’ve got an email system in place, in the instance of phishing – we’ve got an email system in place. We feel like it has the appropriate security controls. But then we miss out the elements of actually making sure that the person is aware or is trained, is provided with the assistive technology around them and then also feels that they’re part of a security culture where they can report these things. So I think that’s also an important factor, too.

Dave Bittner: So one of the interesting results that came through your research here is the impact that stress and fatigue have on workers’ ability to kind of detect these things.

Tim Sadler: Yeah, and this is a really, really important point. So 47% of employees cited distraction as the top reason for falling for a phishing scam. And 41% said that they sent an email to the wrong person because they were distracted. The interesting thing, I think, there is that – another stat that came out from this – 57% of people admitted that they were more distracted when working from home, which is, of course, a huge part of the population now. So this point about distraction seems to play a really important factor in actually the fallibility of people with regard to phishing.

Tim Sadler: And then a further 93% of employees said that they were either tired or stressed at some point during the week. And 1 in 10 actually said that they feel tired every day. And then the sort of partner stat to that, which is important, is that 52% of employees said that they make more mistakes when they’re stressed. And of course, tiredness and being stressed play hand-in-hand. So these are really, really important things for companies to take note of, which is, you have to also think about the well-being of your employees with regard to how that impacts your security posture and your ability to actually prevent these kinds of human errors and mistakes from taking place.

Dave Bittner: Right. Giving the employees the time they need to recharge and making sure that they’re properly tasked with things where they can meet those requirements that you have for them – I mean, that’s an investment in security as well.

Tim Sadler: Completely. And I think what’s really difficult is that security is serious business. No one would doubt or question its importance. It is literally mission critical for companies to get right. Some companies take a draconian approach when it comes to security, and they penalize or they’re very heavy-handed with employees when they get things wrong. I think, again, it is really important to consider the security culture of an organization. And actually, creating a safe space for people to share their vulnerability from a security perspective – things that they may have done wrong – and actually then having a security team or security culture that helps that person with the error or the issue that may arise versus just creating a environment where if you do the wrong thing, then, you know, your job, your role might be in jeopardy.

Tim Sadler: And again, it is a balance because you need to make sure that people are never being careless, and there is a responsibility that we all have in terms of the security posture of our organization. But what this report shows is that those elements are really important. You know, we don’t want to contribute to the distraction. We don’t want to contribute to the stress and tiredness of our employees. And even outside the security domain, if you do have an environment that doesn’t create a balance for your employees, you are at a higher risk of suffering from a security breach because of the likelihood of human error with your employees.

Dave Bittner: All right, Joe, what do you think?

“At Tessian, they believe that people are prone to mistakes, right? Of course we are, right? But why, in the real world, do we act like we're not? That is what struck out to me immediately - the fact that Tim even needs to say this or that somebody needs to say this, that people are prone to mistakes. We act as if we're not prone to mistakes. And then the driving analogy is a great analogy, right? If everybody does everything right in a car, nobody would ever have an accident. But as we all know, that is not the case. ”

Joe Carrigan

Johns Hopkins University Information Security Institute, Co-Host of Hacking Humans

Joe Carrigan: I really liked that interview. Tim makes some really great points. The first thing he says is at Tessian, they believe that people are prone to mistakes, right? Of course we are, right? But why, in the real world, do we act like we’re not? That is what struck out to me immediately – the fact that Tim even needs to say this or that somebody needs to say this, that people are prone to mistakes. We act as if we’re not prone to mistakes. And then the driving analogy is a great analogy, right? If everybody does everything right in a car, nobody would ever have an accident. But as we all know, that is not the case.

Dave Bittner: Accidents happen (laughter). Yeah. I think in public health, too – you know, I often use the example of, you can do everything right. You can wash your hands. You can, you know, be careful when you sneeze and clean surfaces and all that stuff. But still, no matter what, every now and then, you’re still going to get a cold.

Joe Carrigan: Younger people are more likely to say that they’ve made mistakes than older people, and I agree with Tim’s speculation on the disparity of responses across age groups. Younger people have less to lose than an older person who might be more senior in the organization. I also think that an older person might be more experienced with what happens when you admit your mistakes.

Joe Carrigan: And that comes to my next point, which is culture. And that is probably the single-most important thing in a company. And this is my opinion, of course – but this is so much more important when we get to security. It needs to be open and honest, and people need to absolutely not fear coming forward about their mistakes in security. This is something that I’ve dealt with throughout my career, even before I was doing security, with people making mistakes. If somebody tries to cover up a mistake, that makes the cleanup effort a lot more difficult. And it’s totally natural to try to do that. You’re like, oh, I made the mistake. I better correct it. If you don’t have the technical expertise to correct it, you’re actually making more work for the people who have to actually correct it.

Dave Bittner: Yeah. I also – I think there’s that impulse to sort of try to ignore it and hope it goes away.

Joe Carrigan: Right (laughter). That happens, too. I find this is interesting. Men are twice as likely to click on a link than women. Older users are less likely to click on a link. I think that comes from nothing but experience. You and I are older. We’ve had email addresses for years and years and years. I’ve been on the Internet longer than a lot of people have been alive. I know how this works. And younger people may not have that level of experience. Plus, I think younger people are just more trusting of other people. And as we get older, we, of course, become more jaded.

Joe Carrigan: Tech companies have a false sense of security because this is their domain. That’s one of the things Tim said. I think that’s right. You know, that’s not going to happen to us; we’re a tech company. Things are still going to happen to you because, like Tim says very early in the interview, people make mistakes.

Dave Bittner: All right. Well, again, our thanks to Tim Sadler from Tessian for joining us this week. We appreciate him taking the time. Again, the report is titled “The Psychology of Human Error.” And that is our show. Of course, we want to thank all of you for listening.

Dave Bittner: We want to thank the Johns Hopkins University Information Security Institute for their participation. You can learn more at isi.jhu.edu. The “Hacking Humans” podcast is proudly produced in Maryland at the startup studios of DataTribe, where they’re co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. Our coordinating producer is Jennifer Eiben. Our executive editor is Peter Kilpe. I’m Dave Bittner.

Joe Carrigan: And I’m Joe Carrigan.

Dave Bittner: Thanks for listening.