Tessian CTO Ed Bishop runs through the most dangerous forms of spear phishing and email impersonation attacks threatening organizations.

Email allows us to interact freely.

If you know someone’s address, you can send them an email, regardless of where in the world they are located or what device they’re using. Even if you don’t know someone’s email, it’s often relatively easy to guess.

Email is also open by default. This openness has taken masses of friction out of global commerce, and is vital to our businesses. But there’s a tension here. An open network inevitably means risk to individuals and businesses alike.

Organizations around the world handle sensitive material every day. Vigilance will always be important. But striking a balance between empowering employees and cracking down on suspicious activity has to be done sensitively.

Strong-form spear phishing is a particularly dangerous threat. Spear phishing takes advantage of email’s openness using advanced impersonation techniques undetectable by most filters and safeguards, creating significant headaches for information security leaders.

It is the most insidious threat to email communication, and is the number one form of attack threatening enterprises today.

The FBI now tracks Business Email Compromise (BEC), whereby spear phishing is used to extract large sums of money through illegitimate or unauthorized wire transfers. In 2018, the FBI estimated that in the previous five years, Business Email Compromise (of which spear phishing is an important component) had cost enterprises as much as $12.5bn.

So how did this threat emerge?

The birth of phishing

Email was introduced in the 1970s. It didn’t take long for it to attract a parasite: spam, which arrived in 1978.

Spam allowed emails to be sent to large numbers of recipients with minimal personalization. Originally invented for marketing purposes, it soon led to innumerable scams. By 2017, spam made up 55% of all emails received globally.

In response to spam detectors and blockers, attackers started to work harder. They turned to phishing.

Phishing mimics the identity of trusted people and services in order to extract sensitive information, such as passwords or account numbers.

Although they remain a threat, generic bulk phishing attacks can usually be prevented by legacy email security solutions.

The problem, though, is that attackers have refined their approach over the years. They have invested more time and energy into targeting specific individuals, and have turned to public-domain information from sites like LinkedIn to personalize emails.

As phishing has grown in popularity, other cybercrime strategies like ransomware and fraudulent online purchases have also become more prevalent. In 2017, hackers stole a staggering £130bn from consumers through these schemes.

And information security professionals have their work cut out. Targeted, personalized attacks are constantly evolving. At Tessian, we see impersonation-based spear phishing as the next stage in this email arms race.

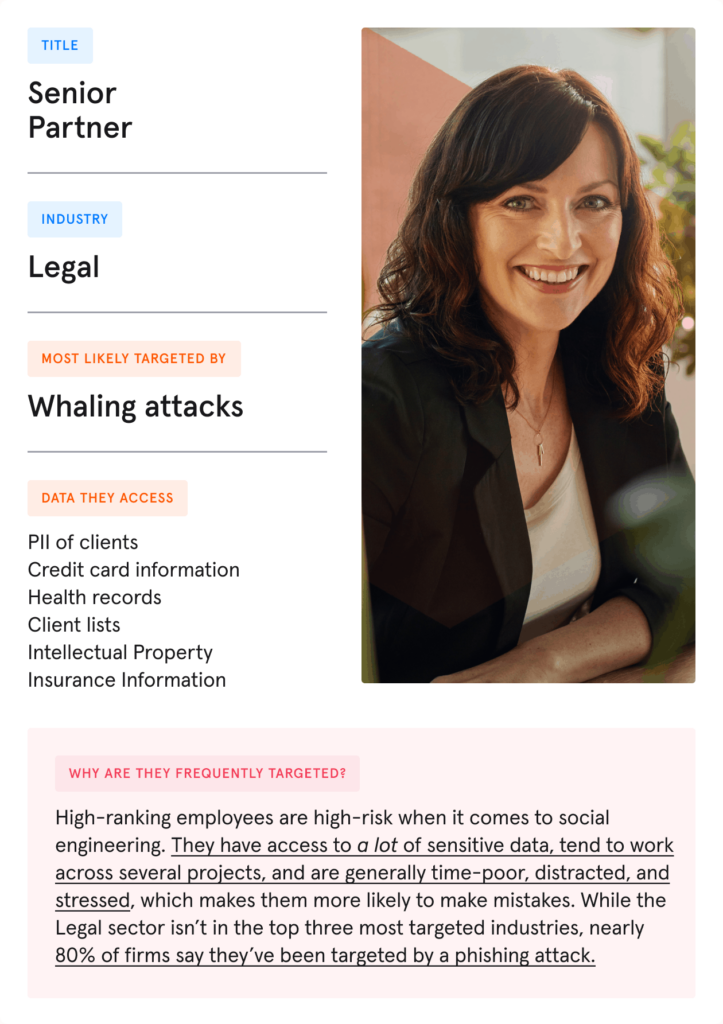

High-ranking employees are most at risk

From a technological perspective, spear phishing is much more difficult to filter out than run-of-the-mill spam or bulk phishing. This is because it is highly targeted towards particular individuals within organizations.

Even the most cynical and risk-aware individuals can be foxed by a spear phishing scam if it is sent on a busy day, delivered in a particular tone, or perceived to be from an authoritative source. Indeed, some threats are confined to IP addresses hidden in email headers – undetectable by employees.

This is not confined to mid-ranking employees: ‘whaling’ scams specifically target C-level executives, for instance. These nefarious tactics are not going away any time soon.

Secure Email Gateways: solving the problem?

To combat attackers, enterprises have traditionally used Secure Email Gateways to monitor attachments and URLs. Today, almost every email provider or legacy Secure Email Gateway (a guard against malicious emails) will include a spam filter. However, there are always ways for attackers to get around these rule-based technologies.

Cybercriminals may employ malware that evades software programs’ screening capabilities, for instance: alternately, organizations might fall victim to a zero-payload attack that doesn’t represent a threat for weeks or months.

So how have Secure Email Gateway structures attempted to address spear phishing issues?

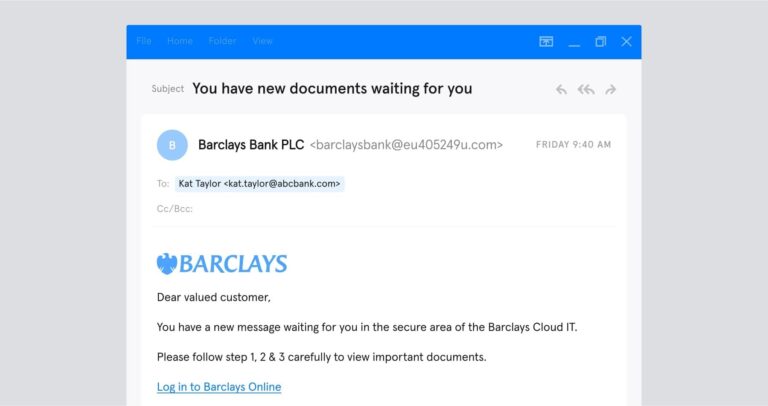

Display address irregularities

Secure Email Gateways are designed to catch irregular display addresses. These occur when the target’s display address doesn’t exactly match the genuine address (changing an ‘n’ to ‘m’ and making ‘bank’ ‘bamk’, for instance).

This check looks for instances where a reply-to address may be different from the sender’s own address.

Domain monitoring

Here, the Secure Email Gateway checks whether the sending domain has been recently registered, or whether it is registered as inactive.

The protective measures mentioned here can only ever be partially effective. That’s because they are focused on providing static, rule-based solutions: attackers can easily reverse engineer these rules and circumnavigate them.

So how are cybercriminals evading Secure Email Gateways? At least in part by focusing on strong-form techniques.

Attackers are becoming more subtle

Attackers have a variety of ways to break down organizations’ defences, but strong-form tactics are especially hard for Secure Email Gateways and other rule-based systems to detect.

We’ve already covered reply-to modifications, for instance. This is an example of weak-form phishing which relies on targets not realising that the reply-to address of an email has been changed from the original ‘sender’. With strong-form phishing tactics, the reply-to address can appear to be exactly the same as the sender’s address. This has the potential to confound simplistic rule-based systems.

A strong-form attack could be a homograph impersonation of a ‘trusted’ external counterparty, such as a law firm or an accountant. Here, other alphabets can be used to deceive targets into believing a domain or address is genuine. The English language ‘a’, for instance, is very similar to a Cyrillic small letter ‘a’. This visual trick can be used to create alias addresses that could well deceive targets.

It might seem surprising that anybody can send an email pretending to be anyone, but current email protocols allow for this. Email authentication methods like SPF, DKIM and DMARC have been designed to try and confirm sender identities. The problem is that this can only be truly effective when every company in the world publishes its own email authentication record. Unfortunately, this is far from being the case: many Fortune 500 companies still have not published the recommended email authentication records.

This gives attackers the means to find, through public domain data, any external counterparties without correct authentication records, and simply send emails pretending to be them.

It’s clear that hackers are thinking about more subtle ways to breach organizations’ defences. As such, it’s important to understand how spear phishing works in practice.

The tip of the spear: breaking down intelligent phishing attacks

Understanding how spear phishing attacks are constructed is fundamentally important to the success of an information security team’s defences. So what are the key components of a spear phishing attack?

Target

The target could be any employee within your organization, but attackers may focus on high-ranking executives or members of the finance department. Cybercriminals can spend significant amounts of time researching and identifying the most vulnerable individuals.

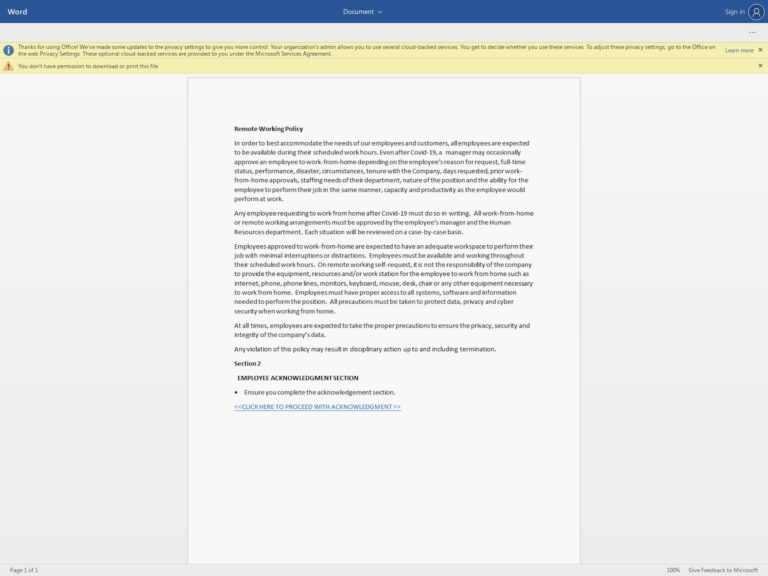

Impersonation

The impersonation of another person or company is the core tenet of spear phishing attacks. Once a target is identified, the attacker may choose to impersonate a colleague or a trusted third party external to the organization (possibly someone who works at another organization they interact with regularly and trust).

Intent

Successful spear phishing attacks all manage to get the email recipient to take a particular kind of action. This could be wiring money to an attacker’s bank account, divulging login details or other sensitive data, or installing malware or ransomware on a device. Often, requests for action exploit organizational pressures to maximize urgency and time sensitivity.